RESEARCH ARTICLE

Bioactive Titanate Layers Formed on Titanium and Its Alloys by Simple Chemical and Heat Treatments

Tadashi Kokubo*, Seiji Yamaguchi

Article Information

Identifiers and Pagination:

Year: 2015Volume: 9

Issue: Suppl 1-M2

First Page: 29

Last Page: 41

Publisher ID: TOBEJ-9-29

DOI: 10.2174/1874120701509010029

Article History:

Received Date: 6/6/2014Revision Received Date: 26/8/2014

Acceptance Date: 27/8/2014

Electronic publication date: 27/2/2015

Collection year: 2015

open-access license: This is an open access article licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/) which permits unrestricted, non-commercial use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the work is properly cited.

Abstract

To reveal general principles for obtaining bone-bonding bioactive metallic titanium, Ti metal was heat-treated after exposure to a solution with different pH. The material formed an apatite layer at its surface in simulated body fluid when heat-treated after exposure to a strong acid or alkali solution, because it formed a positively charged titanium oxide and negatively charged sodium titanate film on its surface, respectively. Such treated these Ti metals tightly bonded to living bone. Porous Ti metal heat-treated after exposure to an acidic solution exhibited not only osteoconductive, but also osteoinductive behavior. Porous Ti metal exposed to an alkaline solution also exhibits osteoconductivity as well as osteoinductivity, if it was subsequently subjected to acid and heat treatments. These acid and heat treatments were not effective for most Ti-based alloys. However, even those alloys exhibited apatite formation when they were subjected to acid and heat treatment after a NaOH treatment, since the alloying elements were removed from the surface by the latter. The NaOH and heat treatments were also not effective for Ti-Zr-Nb-Ta alloys. These alloys displayed apatite formation when subjected to CaCl2 treatment after NaOH treatment, forming Ca-deficient calcium titanate at their surfaces after subsequent heat and hot water treatments. The bioactive Ti metal subjected to NaOH and heat treatments has been clinically used as an artificial hip joint material in Japan since 2007. A porous Ti metal subjected to NaOH, HCl and heat treatments has successfully undergone clinical trials as a spinal fusion device.

INTRODUCTION

Various kinds of ceramic such as bioglass, sintered hydroxyapatite, and sintered β-tricalcium phosphate have been found to bond to living bone. They are being already clinically used as important bone substitutes. However, they cannot be used under load-bearing conditions, since their mechanical strength is not equivalent to that of human cortical bone. Under load-bearing conditions, only metallic materials such as stainless steel, Co-Cr-Mo alloys, and titanium (Ti) metal and its alloys are being used as bone-repair materials. However, such materials generally do not bond with living bone and hence their fixation is not stable over long period. In order to confer a bone-bonding capacity to metallic materials, calcium phosphates such as hydroxyapatite have been coated onto their surfaces [1]. However, in most cases the coated layers are not stable in the living body. In contrast to this, to confer bone bonding to a metallic material, we sought to induce apatite formation on the metallic surface in the living body. In the present paper, simple chemical and heat treatments are discussed designed to form a titanate layer that induces apatite formation on the surfaces of Ti metal and its related metals in the living body, as well as their clinical applications.

BACKGROUND OF THE PRESENT CONCEPT

Previously, the present authors reported that A-W glass-ceramics precipitating apatite and wollastonite in a glass matrix bond to living bone through an apatite layer that formed on the surface in the living body. This apatite layer can be reproduced even in an acellular simulated body fluid (SBF) with ion concentrations nearly equal to those of human blood plasma [2]. In addition, it was found that bioglass and sintered hydroxyapatite also bond to living bone through this apatite layer formed in the living body, and that this layer is reproduced even in SBF [2]. Based on these findings, it was postulated that materials with surface apatite formation in SBF also have this capacity in the living body and are able to bond to living bone through the apatite layer.

Subsequently, a titania gel prepared by a sol-gel method was shown to form apatite on its surface in SBF [3].This indicates that Ti metal and its alloys also form apatite on their surfaces in SBF as well as in the living body, and bond to living bone through the apatite layer when their surfaces are appropriately modified. Based on this hypothesis, various kinds of surface modification of Ti metal and its alloys have been proposed for inducing apatite formation and/or bone bonding capability. Ion implantation [4-6], hydrothermal treatments [7-12], electrochemical reactions [13-22] are some examples of these surface modifications. However, they require special equipment and are not readily applicable to large-scale devices of complicated shape or comprised of porous material. In contrast to these methods, simple chemical and heat treatments do not require any special equipment and hence are applicable to a broad range of shapes and materials.

It was reported, that even simple heat treatment is effective to induce apatite formation, as in the case of Ti metal subjected to magnetron sputtering [23] and Ti-15Zr-4Ta-4Nb alloy to micro-grooving [24]. It was also reported, that even simple chemical treatment by H2SO4 [25], HNO3 [26, 27], HF [28, 29], H2SO4/HCl [30, 31] or H2O2/TaCl2 [32] solutions is effective to induce apatite formation and/or bone bonding on Ti metal and its alloys. It was also reported, that heat treatment after chemical treatment with H2O2 [33, 34], H2O2/HCl [35] or H2SO4/H2O2 [36] solutions are effective for inducing apatite formation and/or bone bonding of Ti metal and its alloys. However, these studies have not been performed systematically. Consequently, the general principles governing the apatite formation induced by these treatments are not well understood. We have systematically investigated the chemical and heat treatments effective for inducing apatite formation and bone bonding in Ti and its alloys. The results of these investigations are summarized and reviewed below. Chemical and heat treatments for inducing apatite formation are also mentioned for some metals other than Ti metal.

APATITE FORMATION ON Ti AS A FUNCTION OF THE SOLUTION pH

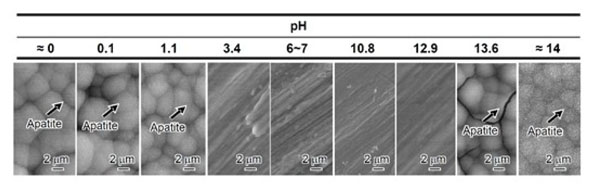

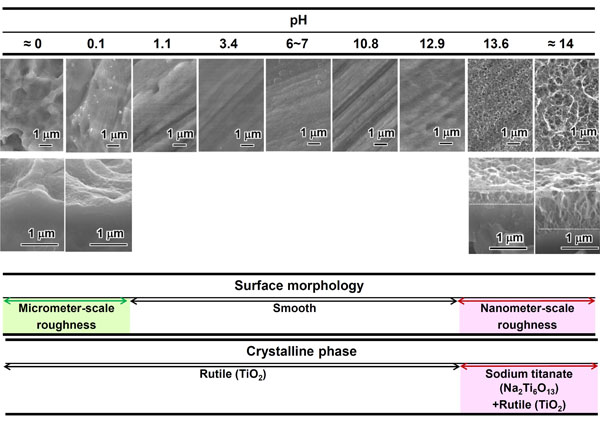

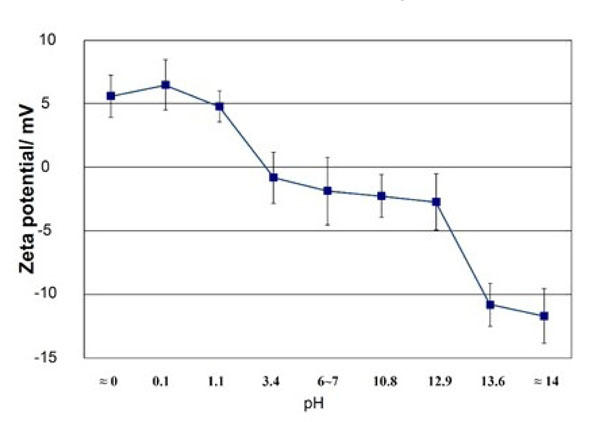

If Ti metal is exposed for 24 hours to aqueous solutions of HCl or NaOH with pH that is changed from almost 0 to 14 at 60 °C, and then heat-treated at 600 °C for 1 h, it forms apatite on its surface in SBF. However, this does not happen when exposed to solutions of intermediate pH levels, as shown in Fig. (1) [37]. The Ti metal formed micrometer- and nanometer-scale roughness, respectively on its surface, when exposed to strongly acidic or alkaline solutions as shown in Fig. (2) [37]. It formed only rutile phase on its surface upon exposure to solutions with pH values below 13, whereas sodium titanate accompanied by a small amount of rutile was formed at pH above 13. In view of these facts, apatite formation on the surface of Ti metal can be ascribed to neither specific surface roughness nor the presence of a specific crystalline phase. When the Zeta potential of the Ti metal subjected to the solution and heat treatments were measured in a NaCl solution it exhibited a high positive or negative potential upon exposure to strongly acidic or alkaline solutions, respectively, as shown in Fig. (3) [37]. This indicates that the apatite formation on the surface of the Ti metal is ascribable to the surface charge.

|

Fig. (1). SEM photographs of surfaces of Ti metal soaked in SBF for 3 days after heat treatment following exposure to solutions with different pH values. Reproduced from Ref [37]. |

|

Fig. (2). SEM photographs of surfaces (top) and cross sections (bottom) of Ti metal heat-treated after exposure to solutions with different pH values, as well as crystalline phases detected on their surfaces. Reproduced from Ref [37]. |

|

Fig. (3). Zeta potentials of Ti metal heat-treated after exposure to solutions with different pH values. Reproduced from Ref [37]. |

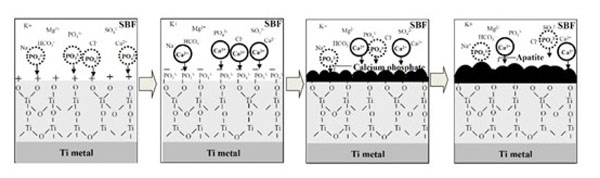

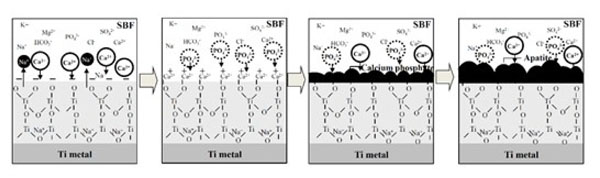

The positively charged surface of the acid-treated Ti metal may first preferentially adsorb negatively charged phosphate ions in SBF. When phosphate ions accumulate, the surface becomes negatively charged and adsorbs positively charged calcium ions to form apatite as shown in Fig. (4) [37, 38]. On the other hand, the negatively charged surface of the alkali-treated Ti metal first preferentially adsorbs positively charged calcium ions and then negatively charged phosphate ions to form apatite, as shown in Fig. (5) [37, 39]. This sequential absorption of the calcium and phosphate ions on the surface of the Ti metal in SBF were experimentally confirmed by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy of Ti metal soaked in SBF for different periods of time, and of surfaces exposed to acidic [38] and alkaline [40, 41] solutions, respectively.

|

Fig. (4). Process of apatite formation on acid-and heat-treated Ti metal. Reproduced from Ref [38]. |

|

Fig. (5). Process of apatite formation on NaOH-and heat-treated Ti metal. Reproduced from Ref [39]. |

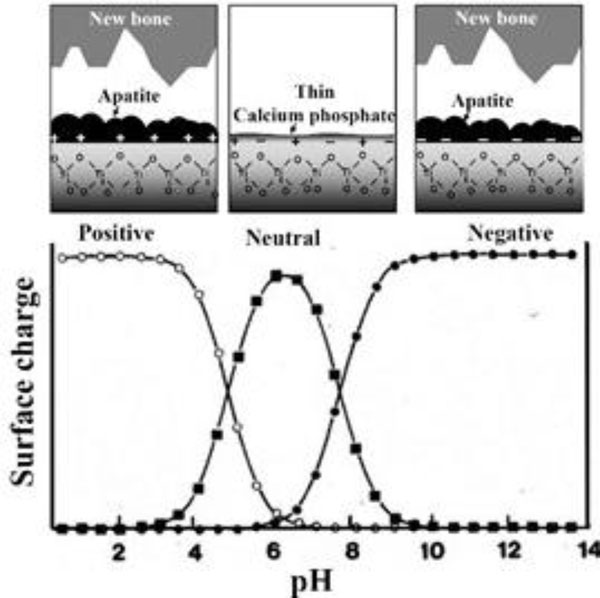

The Ti metal forms titanium hydrides adsorbed with acid radicals on its surface when exposed to acidic solutions [37, 38, 42]. The titanium hydrides are transformed into titanium oxide adsorbed with acid radicals by heat treatment [37, 38]. The acid radicals dissociate in SBF to produce an acidic environment on the titanium oxide. It has been reported, that titanium oxide is positively charged in an acidic solution, as shown in Fig. (6) [37, 43]. Consequently, the surface of the Ti metal heat-treated after exposure to an acidic solution is positively charged.

|

Fig. (6). Surface charges of titanium oxide as a function of pH of exposed solution. Reproduced from ref. 37. The original data were obtained by calculation based on equilibrium among H+, TiOH, TiOH2+ and TiO-. by Gold et al. [43]. |

Likewise, when exposed to a NaOH solution Ti metal forms sodium hydrogen titanate on its surface, which is transformed into sodium titanate by heat treatment [44]. The sodium titanate releases Na+ ions via exchange with H3O+ ions in SBF to produce an alkaline environment at the titanium oxide. It has been reported, that titanium oxide is negatively charged in an alkaline solution, as shown in Fig. (6) [37, 43]. Consequently, the surface of the Ti metal heat-treated after exposure to the alkaline solution is negatively charged.

When the Ti metal was heat-treated after exposure to neutral solutions, it was neither positively nor negatively charged on its surface, as shown in Fig. (3). This indicates that an equal number of positively charged sites and negatively charged sites coexist on its surface. Consequently, negatively charged phosphate ions and positively charged calcium ions are simultaneously adsorbed on its surface so that the respectively charged sites are soon neutralized, as confirmed by XPS [37]. As a result, it forms only a thin calcium phosphate layer, which does not grow into apatite, as shown in Fig. (6).

When the Ti metal was not heat-treated after exposure to the solutions, it was neither positively nor negatively charged, independent of the pH of the solutions. This is because no electrically insulating phase was formed on its surface by the chemical treatment alone, except for sodium hydrogen titanate in the case of the specimens exposed to the solutions with a pH higher than 13. Consequently, they did not form apatite on their surfaces, except for the Ti metals exposed to the solutions of pH above 13 [37].

It is thus clear from these results that Ti metal forms apatite on its surface in SBF upon heat treatment after exposure to strongly acidic or alkaline solutions, since it becomes positively or negatively charged on its surface after these treatments [37]. This predicts that Ti metal will also form an apatite layer on its surface in the living body and bond to living bone through an apatite layer, when it is heat-treated after exposure to a strongly acidic or alkaline solution.

BONE BONDING ABILITY OF T METAL AS A FUNCTION OF SOLUTION pH

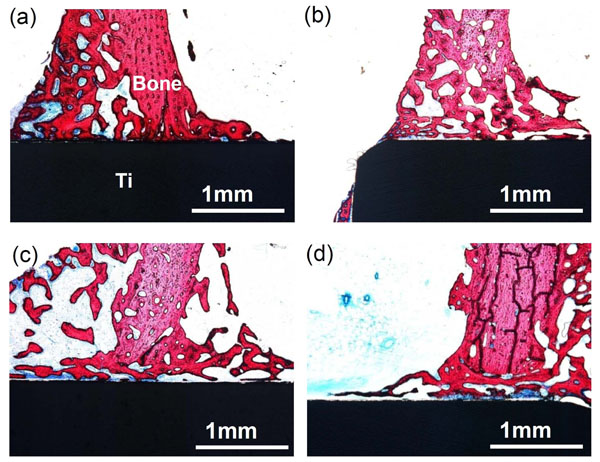

A rectangular Ti metal specimen heat-treated at 600 oC for 1 h after exposure to a strong mixed acidic solution of H2SO4/HCl at 70°C for 1 h was implanted into the tibia of a rabbit. Within 4 weeks, the specimen came into direct contact with the surrounding bone without any intervening fibrous tissue. However, the specimens that had been heat-treated after exposure to only pure water, as well as those not heat-treated after exposure to either water or a strongly acidic solution, were encapsulated by fibrous tissue, as shown in Fig. (7) [45]. When tensile stress was applied to the interface between the specimen, heat-treated after exposure to the strongly acidic solution, and the bone, fracture did not occur at the interface but occurred through the bone.

|

Fig. (7). Optical micrographs of non-decalcified sections of Ti metals acid-and heat-treated (a), water-and heat-treated (b), as-water-treated (c), and as-acid-treated (d), 4 weeks after implantation into the tibia of rabbits. Reproduced from Ref [45]. |

In the case of dental implants, only sandblasting or acid etching was applied to the Ti metal in most cases, for the purpose of obtaining osteointegration [46]. However, the present results show that bonding of the Ti implant with the surrounding bone cannot be realized without subsequent heat treatment.

When a porous specimen of Ti metal was implanted into the femoral condyle of a rabbit, the specimen that had been heat-treated after exposure to the strongly acidic solution became deeply penetrated by newly grown bone within 3 weeks. However, specimens heat-treated after exposure to only pure water as well as those not heat-treated after exposure to water or acidic solution were only slightly penetrated by newly grown bone, as shown in Fig. (8) [47].

|

Fig. (8). Optical micrographs of non-decalcified sections of porous Ti metals acid-and heat-treated (a), water-and heat-treated (b), as-water-treated (c), and as-acid-treated (d), 3 weeks after implantation into the femoral condyle of rabbits. Reproduced from Ref [47]. |

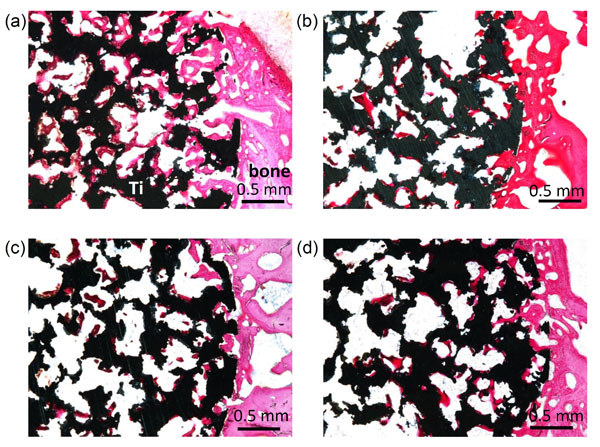

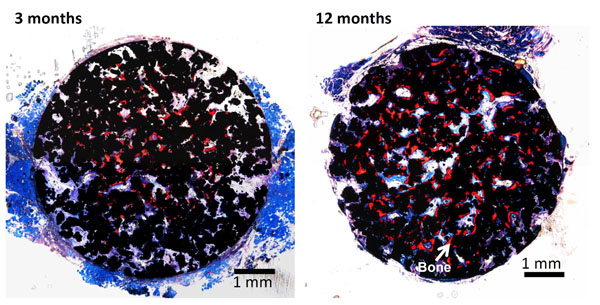

When identical porous specimens of the Ti metal were implanted into a dorsal muscle of a beagle dog, the specimen that had been heat-treated after exposure to a strongly acidic solution formed new bone tissue, ectopically in its porous region, within 12 months. However, specimens heat-treated after exposure to only pure water, as well as those not heat-treated after exposure to either water or strongly acidic solution, formed no bone, as shown in Fig. (9) [48].

|

Fig. (9). Optical micrographs of de-calcified sections of porous Ti metals acid-and heat-treated (a), water-and heat-treated (b), as-water-treated (c), and as-acid-treated (d), 12 months after implantation into the muscle of dogs. Reproduced from Ref [48]. |

These results show, that Ti metal heat-treated after exposure to strongly acidic solution exhibits not only bone bonding ability and osteoconductivity, as expected by apatite formation in SBF, but also osteoinductivity.

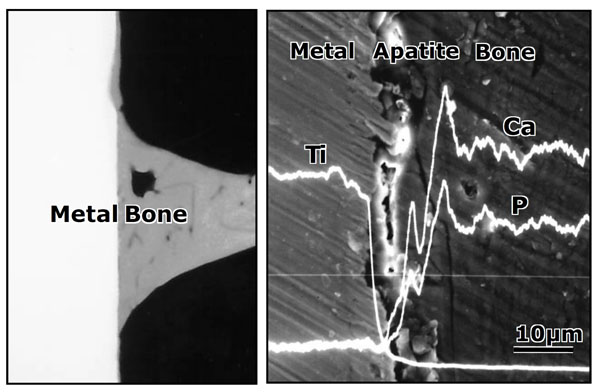

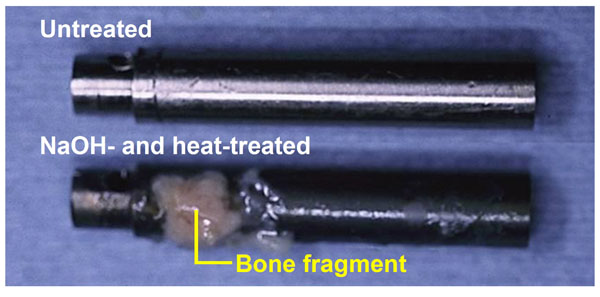

Likewise, a rectangular Ti metal specimen, heat-treated at 600 °C for 1h after exposure to a strongly alkaline solution of 5 M NaOH at 60 °C for 24 h, and implanted into the tibia of a rabbit was found to form an apatite layer on its surface. The specimen came into contact with the surrounding bone through the apatite layer, without any evident fibrous tissue, within 8 weeks, as shown in Fig. (10) [49]. When a Ti metal rod, heat-treated after exposure the NaOH, was implanted into the medullary canal of the rabbit femur, the specimen could not be pulled out after 12 weeks of implantation without accompanying bone fragments, as shown in Fig. (11) [50].

|

Fig. (10). Contact radiomicrograph (left hand) and SEM photograph (right hand) of Ti metal heat-treated after exposure to NaOH solution at its interface with the bone, 8 weeks after implantation into the tibia of rabbits. Reproduced from Ref [49]. |

|

Fig. (11). Titanium metal rod heat-treated after exposure to NaOH solution, which was pulled out from the medullary canal of a rabbit, 12 weeks after implantation, in comparison with an untreated rod, after Ref [50]. |

When a porous specimen of the Ti metal was implanted into a rabbit femoral condyle, the specimen that had been heat-treated after exposure to the NaOH solution became deeply penetrated by newly grown bone within 4 weeks, whereas a specimen not heat-treated after exposure to water was only slightly penetrated by newly grown bone [51].

When an identical porous specimen of the Ti metal was implanted into the dorsal muscle of a beagle dog, the specimen that had been heat-treated after exposure to the NaOH solution also formed a new bone tissue ectopically in its porous structure within 12 months, but only to a small amount [52].

These results show that a Ti metal heat-treated after exposure to a strongly alkaline solution exhibits bone bonding ability and osteoconductivity, as expected from the apatite formation on its surface in SBF. However, its osteoinductivity was very small, in contrast with the specimen heat-treated after exposure to a strongly acidic solution.

Tsukanaka et al. recently observed active proliferation and differentiation of osteoblasts around Ti metal heat-treated after exposure to NaOH solution using fluorescent mouse osteoblasts in vivo [53].

Hence, the general principle governing the bone-bonding capacity of Ti metal is clear as evidenced from these results. A bone-bonding Ti metal can be obtained by simple heat treatment after exposure to a strongly acidic or alkaline solution, since it becomes charged positively or negatively on its surface thus able to form an apatite layer.

MODIFICATION OF ACID AND HEAT TREATMENT OF T AND ITS ALLOYS

The general principle governing the bone bonding ability of Ti metal described above is also basically valid for Ti-based alloys. However, some modification is required of the chemical and heat treatments in order to obtain bone bonding alloys, since the alloying elements tend to disturb the outcome. For example, alloying elements tend to form oxides different from titanium oxide on the surface of the alloys after the acid and heat treatments that suppress apatite formation on their surfaces in either SBF or the living body. In these cases, if the alloys are first exposed to the NaOH solution to remove the alloying elements from their surfaces, the acid and heat treatments are effective. For example, when Ti-15Zr-4Nb-4Ta alloy was preliminarily exposed to the NaOH solution, it formed a positively charged titanium oxide layer after HCl and heat treatments, and subsequently apatite on its surface in SBF [54].

The acid and heat treatments after exposure to a NaOH solution have some benefits even for pure Ti metal, since they form a titanium oxide surface layer with a nanometer-scale roughness in a highly specific area after these treatments, in contrast with the titanium oxide surface layer with a micrometer-scale roughness produced by direct acid and heat treatments. When the Ti metal is first exposed to a NaOH solution, it forms a sodium hydrogen titanate surface layer with a nanometer-scale roughness. The sodium hydrogen titanate is transformed into hydrogen titanate by subsequent acid treatment [55] and then into titanium oxide by subsequent heat treatment [56], retaining the nanometer-scale roughness on its surface as long as the acid concentration is not too high [57].

The Zeta potential of the surface titanium oxide layer increases with increasing concentration of the acidic solution used to increase apatite formation on its surface in SBF, irrespective of the type of acidic solution used [57].

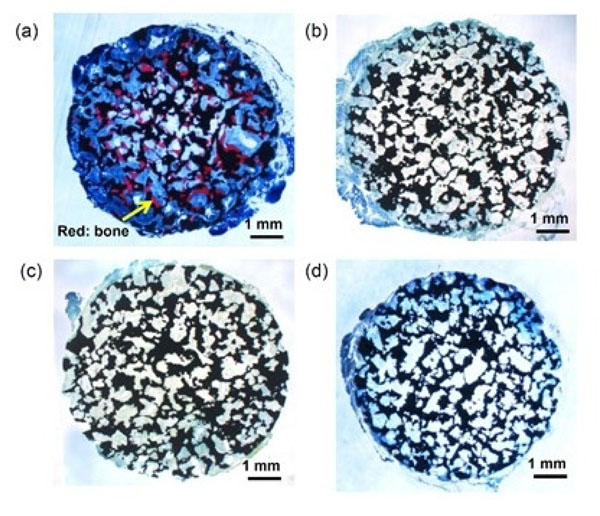

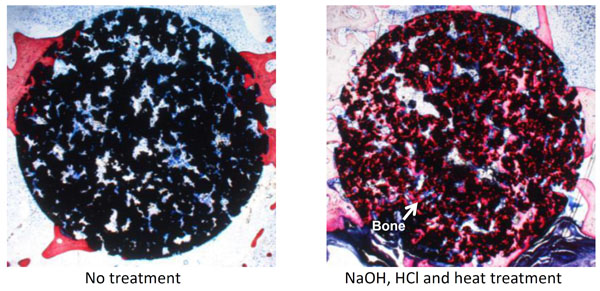

As described above, porous Ti metal subjected to NaOH and heat treatment exhibited little osteoinductivity. This might be attributed to the sodium ions released from the sodium titanate surface layer, which increase the local pH in the narrow space of the pores, suppressing bone formation. When the HCl and heat treatments were applied to the porous Ti metal after the NaOH treatment, a positively charged titanium oxide layer with a nanometer-scale roughness formed on the inner surface of the pore, resulting in the high osteoinductivity shown in Fig. (12) [52, 58, 59] as well as osteoconductivity, as shown in Fig (13) [60, 61]. Zhao et al. have independently reported the osteoinductivity of the Ti metal subjected to NaOH, HCl and heat treatments [62]. The porous Ti metal used for this purpose can be produced by sintering of Ti metal powders containing volatile materials [63] or 3D-selective laser melting of Ti metal powders [61, 64].

|

Fig. (12). Optical micrographs of de-calcified sections of porous Ti metal subjected to NaOH, HCl and heat treatments, 3 and 12 months after implantation into the muscle of a dog. Reproduced from Ref [52]. |

|

Fig. (13). Optical micrographs of de-calcified sections of porous Ti metal untreated and subjected to NaOH, HCl and heat treatments, 26 weeks after implantation into a rabbit femur, after Ref [60, 61]. |

MODIFICATION OF NaOH AND HEAT TREATMENT OF Ti AND ITS ALLOYS

Gil et al. showed that the apatite-forming ability in vitro [65] as well as in vivo [66] and also the bone-bonding of the Ti metal heat-treated after exposure to the NaOH solution can be increased by preliminary sand-blasting of the Ti metal.

The NaOH and heat treatments are effective not only for pure Ti metal, but also for conventional Ti-based alloys such as Ti-6Al-4V [67-69], Ti-6Al-2Nb-Ta [67, 69] and Ti-15Mo-5Zr-3Al [67, 69]. These alloys induce apatite formation on their surfaces in SBF and bone bonding, since alloying elements such as Al, V and Mo are selectively released from the surface by the NaOH treatment. However, these simple treatments are not effective for certain new kinds of alloy of the type Ti-Zr-Nb-Ta, which are free of elements suspected of cytotoxicity such as Al and V, since the alloying elements Zr, Nb and Ta are hardly released by the NaOH treatment, suppressing apatite formation in SBF or the living body [54].

In addition, these simple treatments also have the following problems. Even the small amount of calcium ions contained in commonly used NaOH reagent enters into the sodium titanate formed on the Ti metal and its alloys by these treatments, suppressing surface apatite formation in SBF or the living body [70]. The sodium titanate formed on the Ti metal and its alloys by these simple treatments tends to lose its sodium ions during storage in a humid environment due to the exchange of the sodium ions with H3O+ ions in the moisture, resulting in decreased surface apatite formation [71].

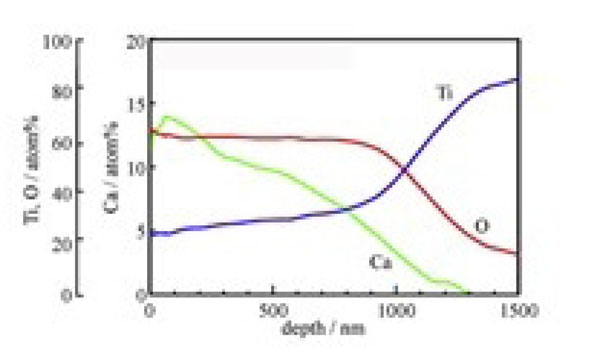

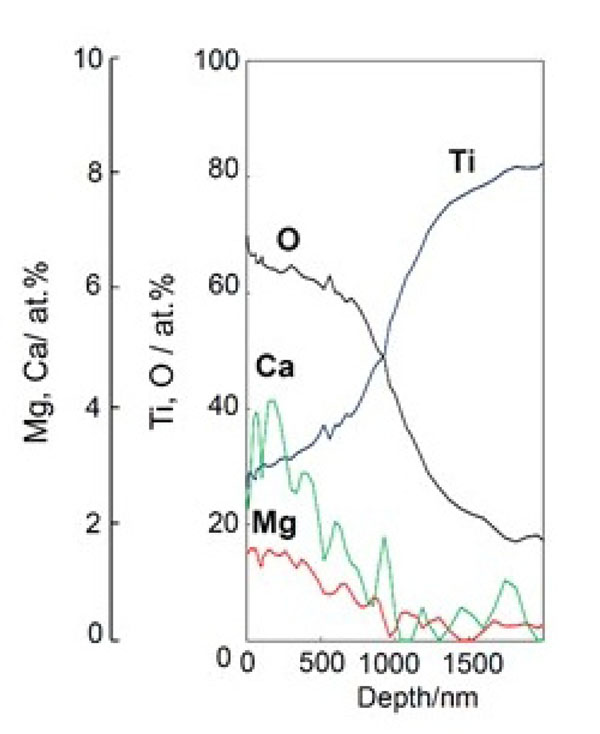

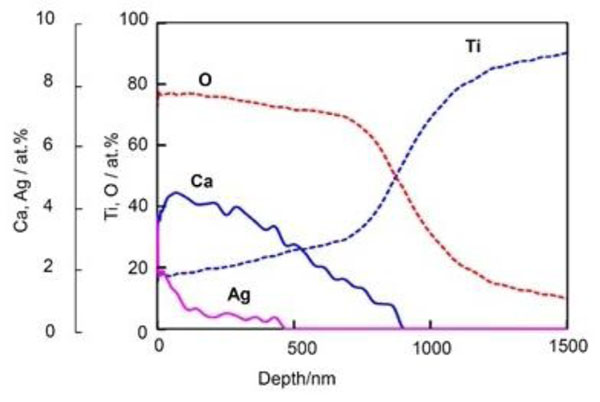

All these problems of the simple NaOH and heat treatments would be solved if the sodium titanate could be replaced with calcium titanate. Unfortunately, calcium titanate cannot be formed on Ti metal or its alloys by simple Ca(OH)2 solution and heat treatments, since the solubility of Ca(OH)2 in water is very low. If the Ti metal is soaked in 100 mM of CaCl2 solution at 40 °C for 24 h after the NaOH treatment, the Ca2+ ions completely replace the Na+ ions in the sodium hydrogen titanate formed by the NaOH treatment with calcium titanate and form by the subsequent heat treatment. This calcium titanate forms hardly any apatite on its surface in SBF, since it scarcely releases any calcium ions. However, if the Ti metal is subsequently exposed to hot water at 80 °C for 24 h, the Ca2+ ions on the surface of the calcium titanate are partially replaced by the H3O+ ions in the water to form a Ca-deficient calcium titanate on its surface, as shown in Fig. (14) [72]. Consequently, the rate of the Ca2+ ions release from the Ti metal is increased, increasing the apatite formation on the Ti metal. The apatite-forming ability conferred by these treatments is maintained even after storage in a humid environment for a long time [72].

|

Fig. (14). Depth profile of Auger electron spectroscopy of Ti metal subjected to NaOH, CaCl2, heat and water treatments. Reproduced from ref [72]. |

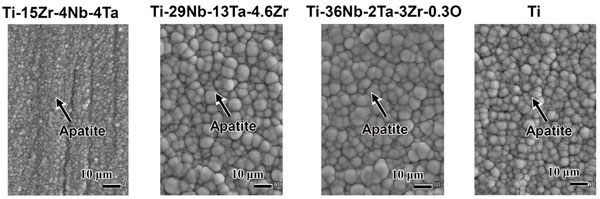

These treatments are effective not only for pure Ti metal, but also for new kinds of Ti-based alloy such as Ti-15Zr-4Nb-4Ta, Ti-29Nb-13Ta-4.6Zr and Ti-35Nb-2Ta-3Zr-0.3O alloys to induce apatite-forming ability in SBF, as shown in Fig. (15) [72-74]. The apatite-forming capacity conferred by these treatments is maintained even after storage in a humid environment for a long period [73].

|

Fig. (15). SEM photographs of surfaces of Ti metal and Ti-Zr-Nb-Ta alloys subjected to NaOH, CaCl2, heat, and water treatments, after soaking in SBF for 3 days. Reproduced from Ref [73, 74]. |

Sawada et al. reported that when 10 mM Ca(OH)2 solution replaced the100 mM CaCl2 solution during these treatments, the apatite formation of the Ti metal increased [75]. However, it should be noted that Ti metal that was chemically treated, but not subsequently heat-treated, had only a low level of scratch resistance [72].

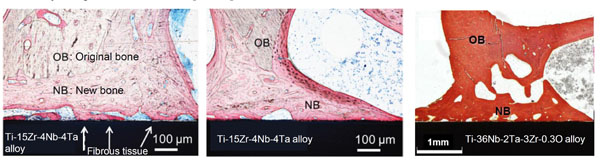

Ti metal as well as its alloys with Ca-deficient calcium titanate formed on their surfaces by the NaOH, CaCl2, heat, and water treatments were confirmed to tightly bound to the surrounding bone without any fibrous tissue intervening at the interface with the bone, as shown in Fig. (16) [76, 77], as expected from the surface apatite formation in SBF.

|

Fig. (16). Optical micrographs of Ti-Zr-Nb-Ta alloys subjected to NaOH, CaCl2, heat and water treatments at their interfaces with the bone, 16 weeks after implantation into the tibia of a rabbit, in comparison with an untreated specimen (left hand specimen). Reproduced from Ref [76, 77]. |

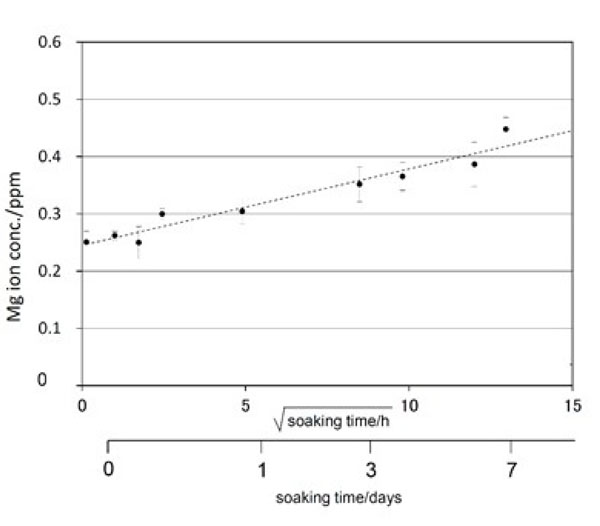

If the NaOH, CaCl2, heat and water treatments are slightly modified, various kinds of functional ion such as Mg2+, Sr2+, or Zn2+ ions, which are known to promote bone growth, can be incorporated into the surface calcium titanate layer. When the Ti metal or its alloys were soaked in CaCl2 solution containing Mg2+ [78], Sr2+ [79], or Zn2+ [80] ions after the NaOH treatment, and then subjected to the heat treatment and a final hot water treatment, layers of calcium titanate incorporating these functional ions were formed on their surfaces. When aqueous solutions containing functional ions were used instead of pure water at the final stage, a larger amount of functional ions was incorporated into the surface calcium titanate layer, as shown in Fig. (17) [78]. The resultant products not only formed apatite on their surfaces in SBF, but also slowly released the functional ions into phosphate-buffered saline at 36.5 °C, as shown in Fig. (18) [78-80]. These ions will be released from the Ti metal also to the living body to promote growth of the surrounding bone. Consequently, an early bonding of the Ti metal with the surrounding bone will take place.

|

Fig. (17). Depth profile of XPS of Ti metal subjected to NaOH, CaCl2/MgCl2, heat, and MgCl2 treatments. Reproduced from Ref [78]. |

|

Fig. (18). Mg ion release from Ti metal subjected to NaOH, CaCl2/MgCl2, heat, and MgCl2 treatments into phosphate-buffered saline at 36.5 °C. Reproduced from Ref [78]. |

When Ti metal or its alloys were soaked in AgNO3 solution instead of pure water at the final stage of the NaOH, CaCl2, heat, and water treatments, an Ag-containing calcium titanate layer was formed on the Ti metal surface, as shown in Fig. (19) [81]. The resultant product not only formed apatite on its surface in SBF, but also slowly released the Ag+ ions into the fetal bovine serum that exhibited antibacterial activity. The Ag+ ions are expected to be released from the Ti metal in the living body to prevent infection.

|

Fig. (19). Depth profile of Auger electron spectroscopy of Ti metal subjected to NaOH, CaCl2, heat, and AgNO3 treatments. Reproduced from Ref [81]. |

CHEMICAL AND HEAT TREATMENTS FOR INDUCING APATIITE FORMATION ON METALS OTHER THAN Ti METAL

A zirconia gel prepared by a sol-gel method also formed apatite on its surface in SBF within 3 days, when heat-treated at 600 or 800 °C [82]. This indicates that zirconium metal is able to form apatite in SBF when its surface is chemically slightly modified. However, a zirconium metal plate formed apatite only scarcely on its surface in SBF even after 28 days, when it was treated with 5-15 M NaOH solution at 95 °C for 24 h [83]. Chen et al. [84] reported that a zirconium metal plate produced by sintering of metal powders formed apatite on its surface in SBF within 7 days, when soaked in 10 M NaOH solution at 60 °C for 24 h and then heat-treated at 600 °C for 1 h in vacuum.

A niobium oxide gel prepared by a sol-gel method also formed apatite on its surface in SBF within 7 days [85]. However, niobium metal did not form apatite on its surface within 14 days when treated with 0.5-2.0 M NaOH solution at 60 °C for 24 h [85]. Treatment by NaOH solution with concentrations higher than 2 M produced cracks at the metal surface. Wang et al. [86] reported that niobium metal forms apatite on its surface in SBF within 7 days when soaked in 0.5 M NaOH solution at 80 °C for 24h, and then heat-treated at 600 °C for 1 h in vacuum.

A tantalum oxide gel prepared by a sol-gel method also formed apatite on its surface in SBF within 7 days [87]. Tantalum metal formed apatite on its surface in SBF without any surface chemical modification [88]. However, whereas it required an induction period as long as 4 weeks for apatite to form, apatite was formed on a sodium tantalate hydrogel surface layer within 7 days when treated with 0.2-0.5 M NaOH solution at 60 °C for 24 h, and subsequently heat-treated at 300 °C for 1 h. The bonding strength of the surface layer to the substrate increased without any decrease in its apatite-forming ability [89, 90]. The reason why the NaOH treatment enhanced the apatite-forming ability was interpreted in terms of apatite nucleation induced by Ta-OH groups formed on the Ta metal in SBF [91]. The tantalum metal subjected to the 0.5 M NaOH treatment and 300°C heat treatment was confirmed to be strongly bonded to the living bone without intervention of the fibrous tissue at the interface to the bone within 16 weeks by animal experiments using a rabbit model [92].

However, in contrast to the results above, an alumina gel prepared by a sol-gel method did not form apatite on its surface in SBF [3], this indicates that Al metal femoral condyle on its surface even if its surface was chemically modified.

CLINICAL APPLICATIONS OF BIOACTIVE Ti PREPARED BY SIMPLE CHEMICAL AND HEAT TREATMENTS

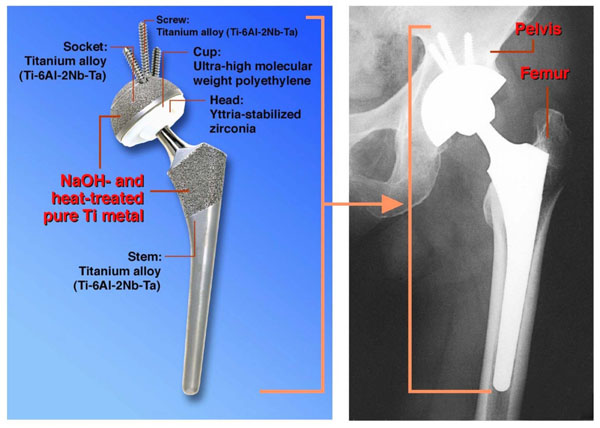

The simple NaOH and heat treatments were applied to a porous Ti metal layer on the acetabular shell and femoral stem of a total artificial hip joint made of Ti-6Al-2Nb-Ta alloy. The resultant bioactive hip joint has been clinically used in more than 10,000 patients since 2007 in Japan [93, 94], as shown in Fig. (20). It was confirmed by two implants that were retrieved 2 weeks and 8 years after implantation, respectively, due to femoral fracture and infection that the implant surface became intimately integrated with newly grown bone as early as 2 weeks after implantation and had maintained this integrity for 8 years [94].

|

Fig. (20). Artificial hip joint, porous Ti metal layer of which was heat-treated after exposure to NaOH solution, after Refs [93, 94]. |

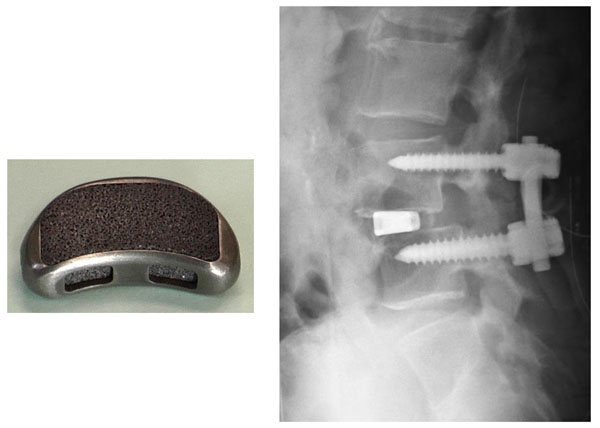

A porous Ti metal subjected to the NaOH, HCl and heat treatments was successfully applied to a spinal fusion device in a canine model [95]. Based on this result, it was subjected to clinical trials as a spinal fusion device for five human patients between November 2008 and June 2009, as shown in Fig. (21) [96]. All these cases had a successful outcome.

|

Fig. (21). Spinal fusion device of porous Ti metal subjected to NaOH, HCl and heat treatments, and its clinical application. Reproduced from Ref [96]. |

It is believed that Ti metal and its alloys that had bioactivity conferred upon them by these simple chemical and heat treatments are useful for a variety of bone-repairing devices used under load-bearing conditions in both the orthopedic and dental fields.

CONCLUSION

- When Ti metal is heat-treated after exposure to HCl or NaOH solutions with different pHs, it forms apatite on its surface in a simulated body fluid when exposed to a strongly acidic or alkaline solution.

- This is because it forms a highly positively charged titanium oxide or highly negatively charged sodium titanate on its surface.

- These Ti metals tightly bond to living rabbit tibial bone.

- The general principle for obtaining bone-bonding Ti metal by chemical and heat treatments is clear from these results.

- Porous Ti metal heat-treated after acid treatment exhibits not only osteoconductivity but also osteoinductivity. However, Ti metal heat-treated after alkaline treatment exhibits only osteoconductivity, since the sodium ions are being released from the sodium titanate into the narrow space of the pores thus hindering osteoinductivity.

- For some kinds of Ti-based alloys, the acid and heat treatments are ineffective to induce apatite formation, since oxides of the alloying elements are formed at their surfaces after the heat treatment.

- However, even those alloys exhibit apatite formation when subjected to acid and heat treatments after a NaOH treatment, since the alloying elements are removed from the surface by latter.

- These acid and heat treatments after NaOH treatment are also effective even for the pure Ti metal. Porous Ti metal subjected to these treatments exhibits not only osteoconductivity, but also osteoinductivity.

- The NaOH and heat treatment is not effective for certain kinds of Ti-based alloy, since the alloying elements suppress the release of sodium ions.

- However, even those alloys exhibit apatite formation when subjected to CaCl2 after NaOH treatments, since Ca-deficient calcium titanate is being formed on their surfaces after subsequent heat and hot water treatments.

- Various kinds of functional ion that promote bone growth, confer antibacterial activity etc., can be incorporated into the surface calcium titanate layer by modified NaOH, CaCl2, heat, and water treatments.

- The bioactive Ti metal subjected to the NaOH and heat treatment has been successfully used as a part of an artificial hip joint since 2007 in Japan.

- A porous Ti metal subjected to NaOH, HCl and heat treatment has undergone successful clinical trials as a spinal fusion device.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors confirm that this article content have no conflict of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTs

All animal and clinical experiments presented in this paper were performed by Professor Takashi Nakamura and his coworkers at the Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Kyoto University, Japan.